Turtles date back to the times of dinosaurs, over 200 million years ago, yet because of changing climate and terribly intense human impact have become a highly vulnerable species today.

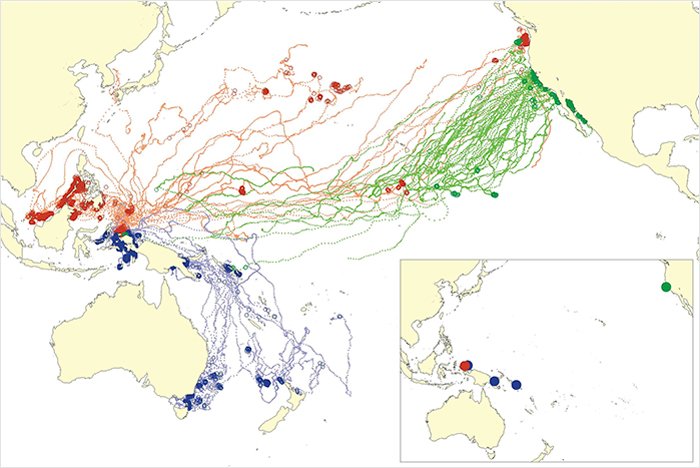

Researchers and volunteers on the Pearl Islands in the Pacific Ocean teamed up to make a positive change. The Leatherback Project, led by marine conservation biologist Callie Veelenturf, is fitting turtles with satellite tags and, by better understanding their habitat, trying to find the best measures to protect them.

The Leatherback Project, led by marine conservation biologist Callie Veelenturf, is helping to protect turtles by fitting them with satellite tags

Turtles are reptiles characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into 2 big groups: the Pleurodira (side-necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden-necked turtles), which differ in the way the head retracts. There are 360 living and recently extinct species of turtles, including land-dwelling tortoises and freshwater terrapins. And no matter how manny animals, from invertebrates to mammals, have evolved shells, none has an architecture like that of turtles: the shell has a top (carapace) and a bottom (plastron).

The most widespread turtles that swim the planet’s waters are: leatherback, loggerhead, Kemp’s ridley, green, olive ridley, and hawksbill. They are found in every ocean except the Arctic and Antarctic. The seventh, the flatback, lives only in the waters around Australia.

Six of the seven sea turtle species are classified as threatened, endangered, or critically endangered, therefore tagging them could provide crucial information about how to protect them

The leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), in other words called the lute turtle, leathery turtle or just simply the luth, is the largest of all living turtles and the heaviest non-crocodilian reptile on earth, reaching lengths of up to 2.7 meters (8 ft 10 in) and weights of 500 kilograms (1,100 lb). Leatherbacks are highly migratory; some of them can swim over 10,000 miles a year between nesting and foraging grounds. They are also accomplished divers, with the deepest recorded dive reaching nearly 4,000 feet—deeper than most marine mammals. The leatherback is also the only sea turtle that doesn’t have an ordinary hard, bony shell: its carapace is flexible and almost rubbery when touched.

According to scientists, six of the seven sea turtle species are classified as threatened, endangered, or critically endangered, due largely to human impact in the form of hunting, bycatch in fishing nets, pollution, and climate change. Slaughtered for their eggs, meat, skin, and shells, sea turtles often suffer from poaching and over-exploitation, as well as facing habitat destruction and accidental capture—known as bycatch—in fishing gear. Climate change has an impact on turtle nesting sites; it alters sand temperatures, which then affects the sex of hatchlings. NOAA mentions that, for example, the global population of leatherback turtles has declined 40 percent over the past three generations. Leatherback nesting in Malaysia has essentially disappeared, declining from about 10,000 nests in 1953 to only one or two nests per year since 2003, therefore there’s definitely a huge need for tools that would help to protect these marine species.

The modern tags can not only show where the turtle is but also can have different sensors depending on what scientists want to study

One of those tools could be satellite tagging, which is a key tool for conservation of wild animals because it can provide crucial information to:

Support the need of conservation and management of Marine Protected Areas;

Facilitate the establishment of multinational agreements for their conservation by showing that marine wildlife does not see international maritime boundaries as humans do;

Help tackle human-caused threats such as bycatch and vessel strikes by pinpointing turtle hotspots;

Understand post-release rehabilitation success.

It’s important to mention that the first study began in 1979 with 4 sea turtles that were fitted with a harness-attached rope that was tied to a buoy, which was equipped with transmitter. It sent the turtle’s location for a maximum amount of 34 days. Nowadays, tracking devices are smaller, lighter and attached directly onto the carapace. They do not harm the animal and the battery life can also be over a year. The modern tags can not only show the turtle’s position but also can have different sensors depending on what scientists want to study.

Marine conservation biologist Callie Veelenturf, together with other researchers and volunteers on the Pearl Islands in the Pacific Ocean, are tagging leatherback sea turtles with satellite tags. The scientists are collecting data on the migratory routes in order to help protect marine species in the region.